In an open letter published this spring, signatories including Elon Musk and Steve Wozniak called for a pause on developing any AI technology more advanced than GPT-4.

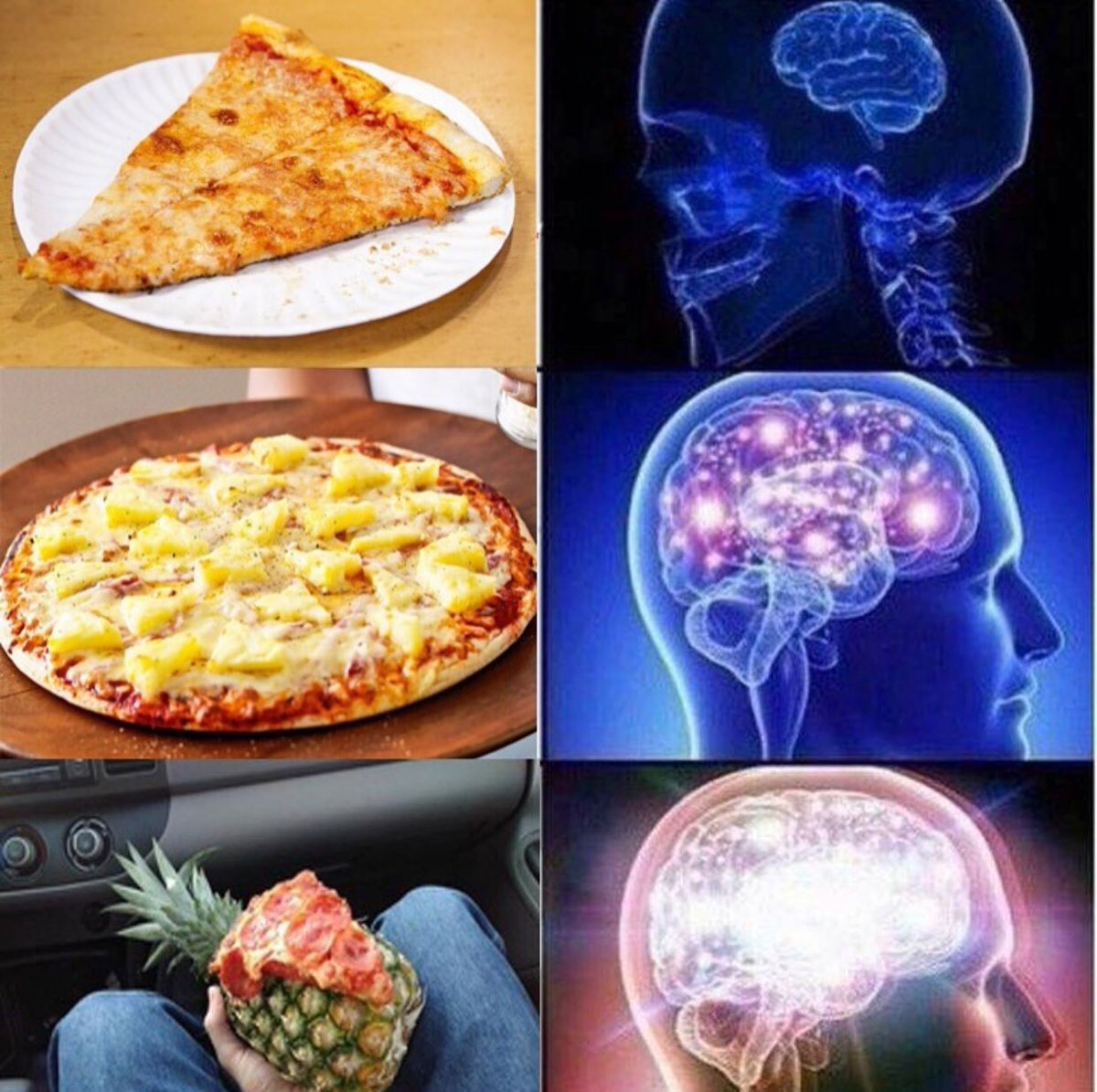

Brain expansion meta meme code#

Chatbots are now generating emails for marketers, code for developers, and grocery lists for home cooks.

Brain expansion meta meme software#

It’s been nearly a year since the research lab OpenAI quietly introduced the demo version of ChatGPT to the public-nearly 12 months of watching the text-generation software and its contemporaries, like Google’s Bard and Meta’s open-source Llama 2, craft poetry and plays, write songs, and solve logic problems. It remains a topic of speculation, imagination, and philosophical inquiry.” “There is no consensus among experts regarding the potential for AI to possess a soul or consciousness. I know my neighbors-the farmer at the market who brings peaches, the dad who works at the Tesla plant-and I know the God that I worship at the church down the street, past the poppies and roses. I see the lemon tree out our window I taste the third-wave coffee brewed in the neighborhood café I feel the salt breeze off the bay. I’m a human, not a bot I perceive and understand the world in a way that the large language model I’m speaking with (and the cars I’m avoiding on the road) cannot. They do not possess subjective experiences or consciousness.” AI systems like ChatGPT are currently designed to simulate human-like conversation and provide useful information based on patterns and data. “As an AI language model,” writes ChatGPT, “I don’t possess personal beliefs, emotions, or consciousness, including the ability to have a soul.

That’s an apt metaphor for our most fulfilling relationships-including our encounters with God, who often meets us in the sacraments of bread and wine, the vibrations of music, and the embraces of other believers.Ī few weeks later, I sit at my desk, speaking to a decidedly unembodied entity. It’s unpredictable, occasionally beautiful. But we also know what we could lose: that feeling of motoring across the Golden Gate Bridge, hands on the wheel, foot on the pedal. We’re hopeful: Self-driving cars, never distracted by their phones, never drowsy, could lower traffic fatalities. The tech is cool, but we don’t quite trust it. “Yes,” I say, “but he looked scared.” The women laugh. Across the street, two women in visors stop to inquire, “Was there someone in that car?” Will the vehicle sense my presence if I dart into the road, or will it decide to plow ahead? Will it be too cautious, refusing to execute the turn at all? Will the hapless human have to intervene? Finally, the car painstakingly inches through the intersection and continues on its way. The car lurches forward, then stops midway. I’m not taking chances that this car, however smart, knows the nuances of pedestrian right of way. I pause at the corner, high-stepping in place. Sure enough, a young man sits in the car. Here, in Palo Alto, I usually see them on test drives, with human operators prepared to intervene if something goes wrong. In San Francisco, fleets of vehicles are already driving around on their own. It’s a self-driving vehicle, collecting data about its surroundings to refine its artificial intelligence. When I’m nearly home, I come across an SUV with whirring sensors affixed to its top and sides, trying to turn left at an intersection, through the crosswalk I’m meant to use. There’s a trickle of water in the creek, temperatures are cooler than previous summers, and we’re optimistic about this year’s fire season. It’s the most beautiful time of year: blossoming orange trees, beds thick with poppies, palm-sized roses in fuchsia and lemon. It’s summer in Silicon Valley, and I’m out for a jog in my neighborhood.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)